Warren Steel: The Day the Machines Went Quiet

Originally founded as the Copper-Clad Steel Company, the company would change its name to the Copperweld Steel Company (CSC) in 1924. Copperweld opened its first facility in 1927, utilizing a former axe factory in Glassport, Pennsylvania. The company went public for the first time in 1929, but shortly after, as the onset of the Great Depression lurked in, its shares were withdrawn. The company hit a huge vein of luck around this same time, when their major client became the United States government, which kept the company in good profitable standing throughout the Depression, and World War II. Having this type of client, the company was able to stay afloat over years, continuing with their second facility at the start of WWII. This is the one we see here today, rusting away in Warren, Ohio. The factory was opened in 1939, manufacturing mainly steel billets. After the war, the recovery and rebirth of the American economy helped the company thrive.

In plans to grow the company, Copperweld would later begin acquisition of other companies, starting with the Flexo Wire Co. in 1951. The company would soon after enter into the steel tube manufacturing business after acquiring the Ohio Seamless Tubing Company. In 1957, Copperweld would merge with Superior Steel Company, a stainless steel finisher, but sold off the division due to 5 years of less-than-favorable performance.

In 1959, Copperweld, alongside Battelle Memorial Institute had developed a second bimetallic product line, branded under the name Alumoweld. Alumoweld was an aluminum-covered steel wire. The product was a success, leading to the company’s first international joint venture in 1966, when they created the Japan Alumoweld Company, located in Numazu, Japan.

By 1972, Copperweld was still acquiring companies and departments, purchasing the Chicago-based Regal Tube division of Lear-Siegler. With this growth would come a name change. With so many companies and diverse divisions under its belt, the decision was made to change the company’s name to the Copperweld Corporation in 1973.

At this time, the company held thousands of employees throughout multiple facilities across the USA, Canada, Japan and Britain. The company was then beginning to move their bimetallic processes beyond just copper and steel, expanding with the use of metals and alloys such as aluminum, tin, brass, gold, nickel and silver.

The company would continue to open yet another new plant in Fayetteville, Tennessee in 1974. This division was known as Copperweld Southern, and it would go on to become the company’s main focus in their bimetallic wire operations.

The first hostile takeover of an American company by a foreign entity would be seen when French holding company Imerys acquired controlling interest of Copperweld Corporation in 1975. Imerys (at the time known as Imétal S.A.) vowed to keep the success of the company on a steady path, and in 1978 would expand its bimetallic wire production to Campinas, Brazil in a joint venture with Erico International Corp. During this same year, the firm announced the layoff of 548 full-time jobs within their Glassport, Pennsylvania facility as the steel crisis of the 1970s began creeping, affecting the company greatly.

In 1980, a new division was created, bringing with it an entirely new revenue stream. The division was known as Copperweld Energy, and had bought stakes in the Houston-based Guardian Oil Company. The plan to begin involvement within the energy business was brought about by a great need for natural gas, ensuring a steady supply for its factories by drilling near its operations in Ohio and Pennsylvania.

The steel crisis crept through the 1980s, still greatly affecting Copperweld, forcing the closure of their Glassport facility entirely by 1983. Only three years later, in 1986, the Oswego fine wire division was also shut down. Both operations were relocated to Copperweld Southern in Fayetteville, as the South offered cheaper labor costs for the company.

In 1986, Imétal would spin off Copperweld’s Warren, Ohio operation (the one we focus on here today) into a separate publicly traded company known as CSC Industries. This company would continue to operate as the Copperweld Steel Company, causing quite a bit of confusion, as now two Copperwelds existed. This paid off, as Copperweld Corporation would return to great profitability only one year after this spin-off, but left CSC in the dust, and by 1993 Copperweld Steel Company went bankrupt.

In 1999, Cleveland-based LTV Steel bought the Copperweld Corporation from Imétal for $650 million, which led to the subsidiary becoming known as LTV Copperweld. At this point in time, the company reigned as largest producer of structural steel tubing in North America, operating 23 plants and employing over 3,500 people across the country. Unfortunately, LTV was still carrying a heavy debt, and at the end of 2000, LTV, along with 48 other subsidiaries, including Copperwelrd, filed for voluntary petitions for relief under Chapter 11 of the U.S. Bankruptcy Code.

In late 2003, LTV Copperweld emerged from bankruptcy, just as Bethlehem Steel of Philadelphia had gone under. Though LTV’s various subsidiaries were sold off, the LTV Copperweld division was able to maintain profitable operations throughout the bankruptcy proceeding. Due to continuing in profitable operations, LTV was able to secure debtor-in-possession financing through GE Commercial Finance, and was able to rise up from their negative financial situation.

Following the company’s filing for bankruptcy in 2000, CSC Ltd. sold off the division at their Warren, Ohio facility for $650 million. Warren Steel Holdings LLC was formed in 2001, taking over the facility, but it would not be until 2007, that the company would begin hiring workers at the plant. This was the same year that the remaining divisions of Copperweld were sold off to Fushi International, thus creating Fushi Copperweld.

Things continued to move well for the Warren Steel, but would eventually fall apart in later years. This brings us to more current years, and the situation, which now sits before us behind the ominous walls of massive structures, rusted pipes and discarded machinery.

In November of 2015, Warren Steel had announced a temporary shutdown of the facility, which had affected around 150 employees. There were plans to reopen early 2016, but with numerous unforeseen circumstances stacking up, operations were unable to be continued as utilities to all buildings were shut off at the beginning of the year. All remaining workers were laid off, and the facilities remain quiet and empty to this day.

With conditions within the steel industry lacking any improvement, the decision had been made to permanently cease operations. This came as a surprise to United Steel Workers.

With a rise in value of the US dollar, there are high levels of imports, putting the industry “under assault” as stated by a worker. Domestic producers are much less easily able to ship steel abroad, while the strong dollar helps aid US companies financially, as they continue to reach out to foreign competitors, for lower shipping costs into the United States, than within.

While demand for steel remains weak, U.S. producers are unable to compete in the market, leading to further closures of more facilities, which used to make up much of the booming industry on this side of the country.

Warren Steel had temporarily halted operations in March of 2014, when energy prices were higher than other similar manufacturers in Ohio. A successful petition run by the company against the Public Utilities Commission of Ohio had brought reduced rates, and the mill was able to reopen in August of 2014.

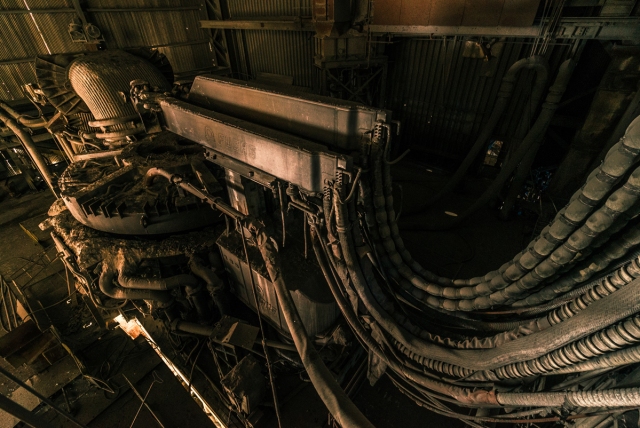

Earlier 2015, the story was greatly different, as Warren Steel had just finished installing new electromagnetic stirrings (EMS) capabilities on its caster. They had – at this same time – announced that they planned, and promised to employ up to 200 full-time workers, and 25 contract workers over the course of the year. This would have increased the company’s entire workforce to 374 people.

During the summer of 2015, things were already going sour for the company, when they were sued in Trumbull County Common Pleas Court by one of their large investors – Vadim Shulman, founder of Bracha Foundation. The company had allegedly deceived Shulman into putting up nearly $30 million as seed money for the venture. The case was dismissed, when the plaintiffs were unable to demonstrate that they were in fact shareholders in Warren Steel.

I visited Warren Steel on a cold day in December of 2016 with my friend Ed. We were lucky enough to sit down with one of the security guards who had worked at Warren Steel for years up to this point. We chatted for a bit about the history of the area, unique and interesting things on the facility grounds, and what things were like during days of operation. It was surely one of the most interesting explorations I have ever been on. There are some days you will remember for a lifetime, and exploration of these abandoned and historic places has given me so many of those – this one included. I think that’s one of the many reasons I like doing this so much.

As I mentioned, it was cold. Of course, it wasn’t just one of those days where you can throw a coat and a pair of gloves on to comfortably enjoy it. Ohio had to give us one of the coldest days that December, luckily on the day we were set to explore and photograph one of the largest industrial facilities in the state. The only thing offering any warmth was the bit of sun near mid-day to later evening. It probably didn’t help that anywhere we ventured into throughout the day was constructed of metal and concrete.

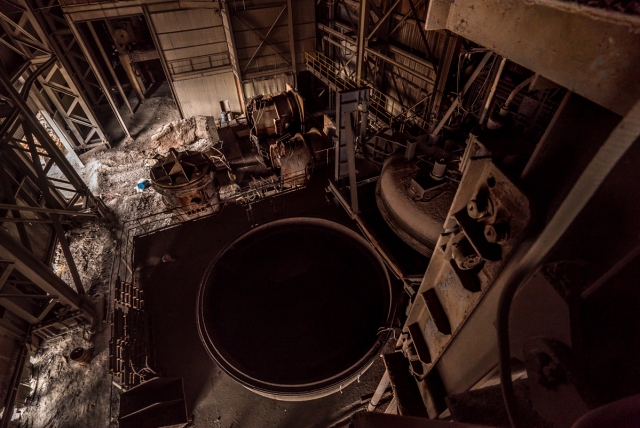

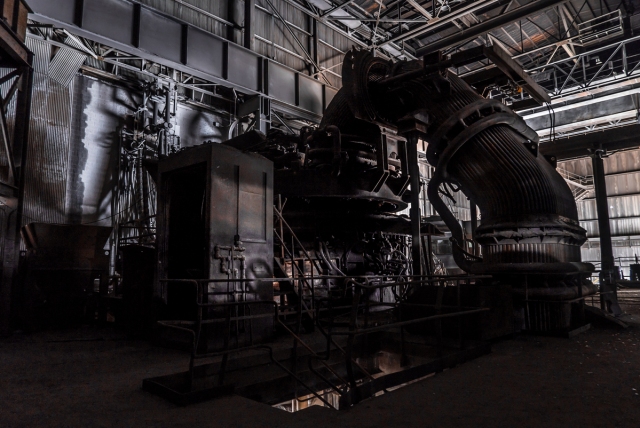

I’ve explored numerous industrial facilities across the country, but have never set foot inside something of such immense size and industrial grandeur left to rot. Hooks formerly used to carry large ladles or other heavy machinery or materials across the factory floor remained on their lines on the ceiling of one building. I have never seen such large hooks in person. It seems like a strange thing to specifically remember, point out and obsess over, but these hooks and chains were large and strong enough to easily carry 25-185 tons across the factory floor. When you climb high up above a factory floor, and stand next to a hook double the size of your entire body, it’s something special. Kind of like an unforgettable birthday party, or traveling back in time to kill Hitler. It’s the simple things.

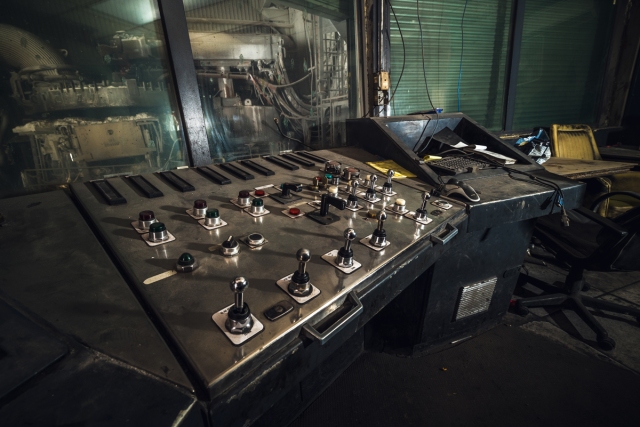

We made our way back down to the factory floor, and into the control rooms. I could truly see how things were left on the day that operations were halted. Objects remained untouched, from computers, to snacks, lunches, gloves and more, now covered in webs and dust in the darkness. As our flashlights passed over control boards, I could picture workers scattering back and forth, operating controls and performing factory duties. The room once so full of life now sat empty and lonely, silently collecting dust.

Our adventure eventually took us to one of the largest abandoned factory rooms I have set foot in. I have never seen a wide open factory floor of such great length, that it seemed to go on forever as it practically disappeared into the distance.

Evening was now upon us, and we planned to utilize every bit of daylight we had for photos. I’ve always been sort of obsessed with the way the evening sun throws itself through windows of an empty space, painting rooms in a bright, warm orange glow. It’s a different kind of peacefulness, when you can feel the warmth of life gleaming through windows, cracks, or holes in walls of a broken place once full of so much life. There’s something so uniquely beautiful about the ethereal glow of the bright orange evening sun complimenting a dark, melancholy scene of abandonment. Amidst the stillness, dust floats, reflecting like glitter, shimmering through sun rays; and just as it has since its final moments of life, the room remains quiet.

View the entire photo gallery in the slideshow below:

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

I have started writing a blog and made a website please not mine is probably no where near as interesting as this one😂 but im just getting started out if you would like then check out my blog. It’s basically life from a twelve year ilds perspective of life and lifestyle stuff x

My husband worked there for 8 years he was so heartbroken when it closed down we all were

You wrote a compelling story i really liked reading it reminded me of the days when i was working at warren steel up untill they layed us off and ultimately closing the doors. 1 thing that would have added to the story is someone that worked in the mill to show you a the routine during a day in the mill from the furnace to the vtd to the caster. Other then that i enjoyed the story.

I worked there during the WSH days. 2011-2013. While I was there, it was simply just the Melt Shop running. There were a few older guys that were hired on by WSH left over from the Copperweld days (may father worked there at that time as an electrician) that would tell us stories of what things were like when the entire property was up and running strong. Although WSH was a less than desirable company to work for, the guys ob the ground were amazing. I still keep in touch with many of them. Some found other jobs in steel, myself included (I live in central PA and work at Standard Steel now). Others are in entirely new fields. But we all have it in our blood now.

And the durable steel we used to know has never been the same since…

Being the amateur I am, I am unable to reblog this because it keeps going to a blogging course I took online. 🙁